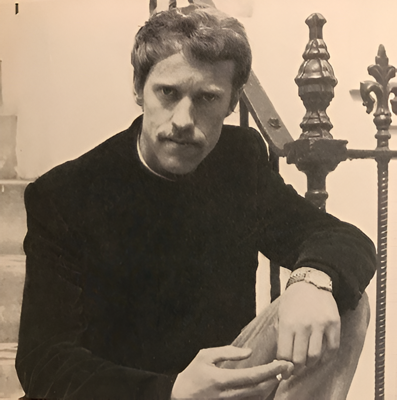

Stroud Cornock

Stroud Cornock was born 1938 and passed away in London in 2019. He was fondly remembered by Ernest Edmonds in this obituary, originally published on the Computer Arts Society website.

It must have been around 1971 when Stroud Cornock told me that he needed to buy a new car. He was very interested in the design and construction of cars, as well as of aeroplanes and boats, so he was well placed to evaluate the competing options. He found, however, that he could not just look at the technology. He said that he needed to think about his life, where he was going, what he was doing, what place a car might take in it. Did he even need a car at all? Stroud took a full systems view of his life and the role of a car in it before making a decision. It was clear to me that Stroud was a deep systems thinker and this was something that underpinned so much of what he did.

Stroud studied sculpture at the Royal College of Art and then joined Roy Ascott's highly innovative team teaching fine art in Ipswich. At this time he was making sculpture in a minimalist style but his growing interest in systems and cybernetics was soon to take him in other directions. In 1968 he moved to Leicester College of Art, soon to be the City of Leicester Polytechnic and now De Montfort University. There he quickly established the Media Handling Area with the explicit goal of making contemporary 20th Century technologies available to fine art students. That was when I first met Stroud.

I was making a large relief and needed to use a technology that I had no skill in and no access to. It was my first encounter with spray painting. I was working in Leicester College of Technology, so I walked across the road to ask if anyone in Art or Design could help. I soon found Stroud who looked after the spray booth amongst the many media facilities that he championed. Not only did he advise me what to do, he was quick to start spraying my work himself, showing enthusiasm and a generosity that I came to learn was central to his personality. It turned out that my need for the spray booth was not what interested Stroud most about my artwork. It was the fact that I had written a computer program to help me complete the design that really set us talking. I think that Stroud had already decided that the computer had to have a key role in art's future. This was the year of the Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition at the ICA.

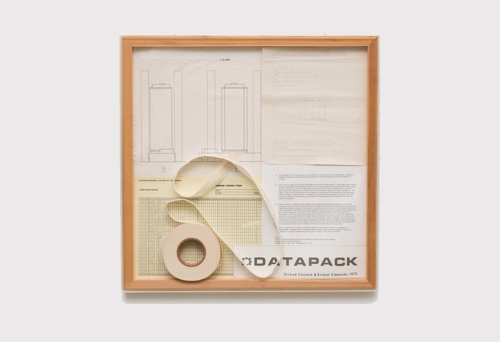

At Leicester, Stroud initiated a series of interactive art proposals, including Interplay, which was presented at the VI Paris Biennale in 1969. He and I worked together on building a working interactive art piece, Datapack, that we showed at the CG70 exhibition, Brunel University. We also presented a paper in the Computer Arts Society stream of the associated conference and later published it in the new journal Leonardo. From hours of discussion, writing that paper, we developed a theory of interactive art, mapping out how we saw the future of art systems in the age of the computer. For me, these were crucially inspiring conversations that in many ways set the path that I have followed ever since.

Stroud never lost his interest in interaction and the use of computers in art. In fact he has made frequent contributions to Computer Arts Society meetings up until very recently. However, as the 1970s projects developed, we were looking for ways of progressing the, much needed, research in that area. Stroud realised that Systems Theory provided a key component and he went to Peter Checkland, Professor of Systems at Lancaster University, to learn more and further this line. Checkland famously promoted a "soft systems methodology" that enabled the study of social systems as part of the field. This led Stroud to look beyond the art system itself and consider the social context, taking a very particular interest in the ways in which art students learn.

When the Polytechnics were formed in the UK (The City of Leicester Polytechnic was founded in 1969) they were not given the direct power to award degrees, as was done in Universities. A national body, the Council for National Academic Awards (CNAA) took this role, overseeing all of those institutions. This was particularly significant in the areas of Art and Design in which degrees had not normally been previously awarded. So the ways in which art students learn was a key concern of the CNAA. It was perhaps not surprising, therefore, that Stroud joined its Registry for Art, Design, Art History and Performing Arts. By the time that the Polytechnics became Universities, with full degree awarding powers, and the CNAA was dissolved, Stroud was the team leader in that Registry. I explained above how he influenced me personally and I know that he also influenced many students directly, but his CNAA work was important for Art and Design education in the UK in general.

Whilst he was at the CNAA, Stroud also recognized that the Council owned a significant number of artworks and he founded the role of curator, ensuring that the collection was properly catalogued and looked after. This wasn't the first curatorial adventure that Stroud undertook. As a schoolboy he began collecting cigarette packets and he curated that intriguing collection throughout the rest of his life. The CNAA's art, however, had to transfer to a new owner once the Council was no more. At that time Stroud transferred to the Open University (OU) where he helped them set up its Validation Services. At the same time the OU took the CNAA art collection over for some years and, again, Stroud took a curatorial interest in the OU's own art collection, taking responsibility for its organization and development.

Eventually, having retired from the OU, Stroud continued to contribute to the maintenance of academic standards in art and design, both as an inspector for the British Accreditation Council and as a consultant. Notwithstanding these contributions, all of the time Stroud has been an active and engaged participant in the latest developments in art thinking and practice, particularly in relation to the "media handling" that he pioneered in Leicester.

Systems of one kind or another may have provided a backbone to Stroud's intellectual life. But as well as this, there was always time for those other important things, such as travel. At times he also put brush to canvas. He took a strong interest in martial arts and was an expert cook. Indeed, not that long ago he added to his influences on me through a gift of a fine book of recipes that was bound to inspire. Positive and active to the end, he ordered a new computer the day before he died.

Stroud was always there, somehow. He was always a pleasure to be with. When I met with Gustav Metzger, a short time before he himself passed away, he only asked one thing of me: "Put Stroud Cornock in touch". Everyone always wanted to talk with Stroud, a kind, generous and highly perceptive friend who I will sorely miss, as will all who knew him.

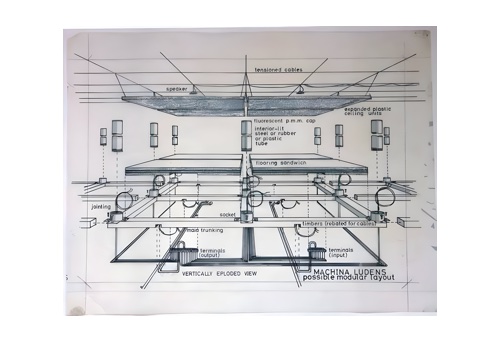

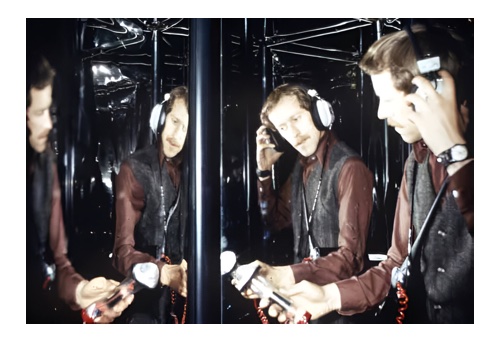

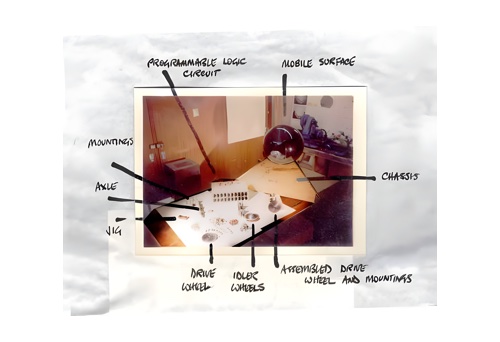

The images in this exhibition are from the interactive computer artwork Datapack 1969; a technical drawing for the interactive space Machina Ludens (1971); Stroud inside the Labyrinth artwork at the Midland Gallery (1971); and the construction of Rover (1971-72) in the Media Handling Area at Leicester Polytechnic.

Artworks

Datapack (1969)

with Ernest Edmonds

Machina Ludens (1971)

Labyrinth (1971)

Rover (1971-72)

Web Links

- Stroud Cornock's Website (Archived)